|

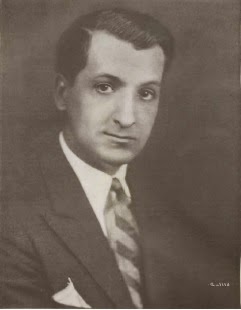

| Alwyn E W Bach |

|

| American Academy of Arts and Letters, Gold Medal for Good Diction |

Alwyn Egbert Winfred Bach was born in 1898 in Worcester, MA to Danish parents who immigrated just two years prior. Eager to become acculturated to their new country, the Bachs made sure that their children gained a good command of the English language. After graduating high school, Alwyn found work in a print shop and as a proofreader, and also honed his skills as a talented baritone singer. When WWI broke out, Alwyn enlisted in the US Army and saw action in the Somme-St. Michel Offensive as part of the 44th Coast Artillery Division.

|

| Bach (sitting, at left) pictured with his troupe during WWI. |

Returning home, Bach settled in Springfield, MA and married Olive C. Murphy. In September 1921, WBZ in Springfield became the first licensed commercial radio station in the country and the following year, the station called upon Bach to sing for one of its programs. Bach’s voice and delivery impressed the producers at WBZ and he was quickly hired as an announcer for the station. In 1926, Bach followed the station in its relocation to Boston and three years later, he was hired away by WNBC, a national syndicate in New York City. Shortly thereafter, he gained renown as a top-rate radio announcer.

The Bachs were now in the hunt to find a home in the New York area. A new development of quaint, Tudor-style homes called Plymouth Colony caught their eye in the up-and-coming Long Island neighborhood of West Hempstead. As an avid tennis player, Alwyn was attracted to Plymouth Colony’s exclusive tennis courts and clubhouse. (The courts were originally located on Sycamore St. and were dedicated on Sunday October 20, 1929, one week before the great stock market crash. The dedication ceremonies included the championship tournament for Brooklyn High Schools. The courts remained for a few years before finally giving way to further subdivision). The Bachs purchased their home at 16 Lindbergh St. (still there at 243 Lindberg St) and quickly became deeply involved in their new community. As the mother of their 7-year old daughter, Joyce Elizabeth, a new student in the Chestnut Street School, Olive ran for and was elected president of the Chestnut PTA.

The following year, in June 1930, Alwyn Bach received radio’s most prestigious prize, the Gold Medal for Good Diction, and was praised for his style and professionalism. Bach had a distinctive low and commanding voice, with a measured and deliberate articulation. At WNBC, Bach offered a good contrast to his more famous colleague, Graham McNamee, who offered a more high-pitched, frenetic and rapid delivery. McNamee was known for broadcasting Yankee games and other events like Lindbergh’s flight across the Atlantic, and his announcing style was more suitable for those types of exciting events. Bach, on the other hand, was assigned to read the intros to radio shows and sponsorship spots, as well as provide coverage to events like the Lindbergh baby kidnapping (and subsequent murder), a riveting episode that had the entire country glued to their radios for two months straight. Bach was a firm adherent to the maxim that an announcer should never interject his or her personal views or feelings when broadcasting a news story. But, as a father himself who lived on a street that, only 4+ years earlier had been renamed for America's aviation hero, he veered slightly from that principle when, after reading out Charles Lindbergh's plea for the safe return of his son, he added, "That is the plea of all of us".

(Although unfortunately most of these early broadcasts were not taped or preserved, Bach’s voice appears in the earliest known NBC station call recording, preceded by the famous thee note C A F chime that NBC still uses to this day. Bach's voice can be heard in a sound clip at a website dedicated to the NBC chime. Scroll about a third of the way down the page.). Bach’s award was celebrated across the country and his reputation spread far and wide.

(Although unfortunately most of these early broadcasts were not taped or preserved, Bach’s voice appears in the earliest known NBC station call recording, preceded by the famous thee note C A F chime that NBC still uses to this day. Bach's voice can be heard in a sound clip at a website dedicated to the NBC chime. Scroll about a third of the way down the page.). Bach’s award was celebrated across the country and his reputation spread far and wide.

Back in West Hempstead, the Great Depression was taking a heavy toll on residents. Many locals had lost their jobs and their homes went into foreclosure. As president of the PTA, Olive Bach organized a welfare fund for needy residents in WH, and leveraged her husband’s connections at WNBC to host a series of concert revues featuring well-known radio personalities, in order to raise money for the new fund. These concerts were held in the Hempstead High School auditorium so that they could accommodate the large turnout,. Though few people today would recognize the names of the featured artists, in 1931 and 1932 they represented a veritable who’s who of headline acts of their time: The Landt Trio, the famous female ukulele player May Singhi Breen and her husband Peter DeRose, The Tasty Yeast Jesters, Stebbins Boys, the famous impersonator Ward Wilson, and on and on. Admission was between 75 cents and $1 and the hundreds of tickets sold at each event raised thousands for the benefit of needy locals during the Depression.

In 1942, Bach was hired by KYW Philadelphia, ending his long run at WNBC. The landscape of broadcast radio was changing. Eight years later, he moved out west to join KNBC San Francisco, until his retirement a few years later. Alwyn Bach died in 1993 in Portland, OR at age 95, a relic from the days when whole families would stop their routines to gather ‘round a beautiful mahogany piece of furniture called the radio to listen to their favorite programs.

No comments:

Post a Comment